Saving regret — and how to avoid it

In November 2018, the National Bureau of Economic Research published a paper called “Saving Regret” [here's the full PDF version]. Once you wade through the study's academic language, there's some interesting stuff here about why people do and don't save for retirement.

Saving regret, the authors say, is “the wish in hindsight to have saved more earlier in life”.

Obviously, you can suffer from saving regret at any age. When I met 31-year-old Debbie for dinner last week, her issues boiled down to saving regret. She wishes she'd saved more when she was younger. But for the purposes of this paper, the authors turned their attention to folks aged 60 to 79, people of traditional retirement age.

The researchers found that two-thirds of those surveyed said they should have saved more when they were working: “66.6 percent said they would save more if they could re-do their earlier life.”

As you might expect, the authors found that high-wealth and high-income people experience less saving regret. (I'm pleased that the researchers recognize that there's a difference between income and wealth.)

But what causes saving regret in the first place? Why don't people save more? Let's take a look at what the study found.

Sources of Saving Regret

In their survey of 1590 people, the authors asked about education, personality, and what they term “positive and negative shocks”. (The latter is basically trying to to determine how unexpected events affect saving.)

After compiling the results, they reached these conclusions:

- “We found only modest evidence for a relationship between our measures of procrastination and the desire to re-optimize saving.” Yes, procrastination is a factor in saving regret. But it's not as big as you might expect.

- Failure to anticipate negative shocks — underestimating their probability and effects — has a greater effect on saving regret.

- Overall, “a substantial percentage of respondents view their economic preparation to be adequate, yet they nonetheless express saving regret.” In other words, as many GRS have experienced, even when you think you have enough saved, you often wish you had more.

“Saving regret is high at the time of or shortly before retirement but is much lower at older ages,” the authors write. They believe there are two reasons for this.

First, when people stop working, they're faced with a lot of uncertainty. This uncertainty makes them long for a larger safety net, makes them wish that they'd saved more. In a sense, this is why I have been experiencing saving regret. When my life was settled, I was fine with my nest egg. But over the past couple of years, there's been a lot of unexpected, unplanned spending. Things seem uncertain. Because of this, I wish I had more saved.

Whether or not there's any actual increased risk to a person's savings, if she feels like there's increased risk, this leads to saving regret.

There's another reason saving regret declines with age: Consumption patterns change. The older people get, the less they spend. This decreased spending leads to greater relief. It lessens the stress.

A Shock to the Savings

Saving regret was greatest among people who always settle for mediocre results (85.8% of these folks experienced regret) and people who always put off difficult things (88.2%), but this is a very small sample of the whole. Plus, these are personality traits that, with effort, can be changed.

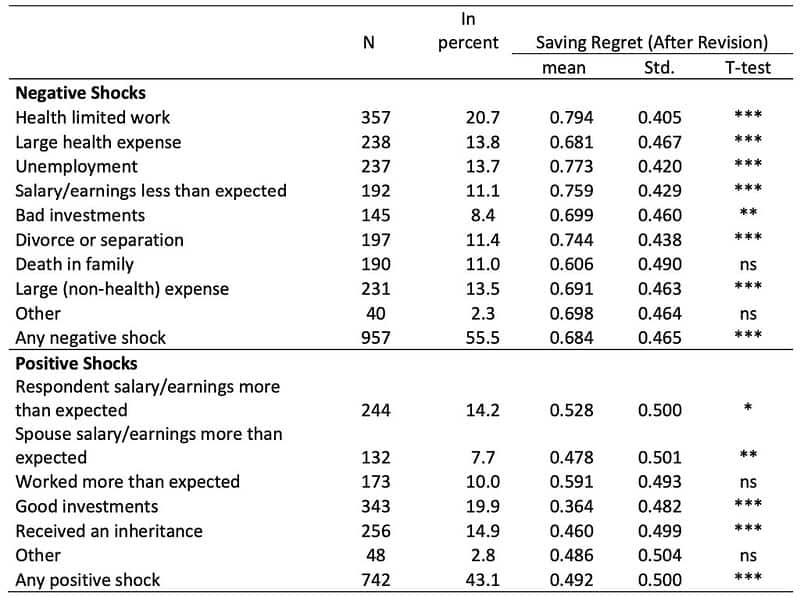

Another huge factor — one that could affect anyone — is what the authors term “economic shocks”. A positive economic shock might be receiving an inheritance. A negative economic shock might be losing your job.

From the paper itself, here's a table demonstrating the relationship between saving regret and economic shocks. (The number you want here is the “mean”. Convert this to a percentage to find out the relationship. For example, the 0.794 listed under mean for “Health limited work” indicates that 79.4% of those whose health affected their ability to work wish they had saved more.)

“Among those with saving regret,” the authors write, “66 percent reported experiencing a shock earlier in life leading to adverse economic consequences, compared with just 43 percent among those without saving regret.”

I found this tidbit interesting too: “Among those with regret, 38 percent reported that Social Security benefits were less than expected compared with just 26 percent among those without regret.” Perhaps it used to be difficult to anticipate Social Security benefits, but nowadays they should never come as a surprise. That info is easy to find.

In a lot of cases, it's not the shock itself that causes the problem. It's the failure to anticipate a possible shock. It's poor preparation.

The authors believe that people tend to be over-optimistic. They “[expect] future outcomes that are better than reasonably likely”. They think they're better than average and will achieve better than average results. Plus, they suffer from the “illusion of control”, an exaggerated belief in their ability to direct their destiny.

This last point is important for me (and many GRS readers).

I am a vocal advocate of becoming proactive. I believe strongly that, to the extent possible, we should all work to manage those parts of our life that fall within our “locus of control”. Some things — the weather, the economy, the actions of other people — are outside of our control, and it's foolish to spend our attention on them. But others — our attitudes, our relationships, our saving rates — are absolutely under our control, and it's foolish to ignore them.

When reading this article, I fretted at first that the authors were arguing that people like me believe we can control more our life than we actually do. I realized, however, that they're actually saying something different: Those who experience saving regret mistakenly believe that people and events in their Circle of Concern actually fall in their Circle of Control.

Money bosses like you and me may not have perfect perceptions of what we can and cannot control, but I believe we have a better understanding than those who express saving regret. We recognize that many things are beyond our control, so we prepare for possibilities. We expect the unexpected.

Avoid Saving Regret

The authors of “Saving Regret” don't delve deep into solutions. Their paper is informational, not prescriptive.

That said, I think the info provided in the paper suggests a handful of solutions to saving regret. If you want to save enough for retirement, do the following:

- Forecast the future. I know it's tough to tell where you'll be in five or ten years. Sometimes, it's impossible. All the same, it's important to try. Having a plan reduces saving regret. The researchers found that “saving regret was highest among respondents who stated that they do not have a financial plan”. The longer a person's planning horizon, the lower their levels of regret.

- Plan for problems. You cannot predict when bad things are going to happen. You don't know if (or when) you're going to get cancer, a drunk is going to crash into your car, or a typhoon will wash away your beach home. You can, however, be relatively certain that something bad will happen sometime. Your best bet is to be prepared — just like a Boy Scout. Maintain an adequate emergency fund.

- Be proactive! There is never ever a reason that your Social Security benefits should come as a shock. The Social Security Administration issues periodic statements about estimated benefits. Plus, it's easy to look up projected benefits online. This is but one example of how you can take steps to prevent future surprises.

- Master your money. “The relationship between saving regret and financial literacy is also strong,” the authors write. People with high levels of financial literacy experienced half as much regret as those at the lowest levels. To avoid disappointment later in life, learn everything you can about personal finance.

- Save more. Yes, this is an obvious solution to saving regret. I get it. But let's make this explicit: Your saving rate — the difference between what you earn and what you spend — is the most important number in your financial life. Saving rate isn't just vital for money nerds who want to retire early. It's a key factor for achieving any financial goal.

Nothing can guarantee your financial future. The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune can wreak havoc on even the best-prepared people. But you can maximize the odds of positive results by taking smart steps now. You can decrease the likelihood that you will experience saving regret by taking action today.

Final Thoughts

If we knew when we were going to die, financial decisions would be much easier.

If I knew, for instance, that I would be mauled by a bear on, say, 04 July 2029, then it would be a simple matter to make sure my retirement nest egg lasted another ten years.

On the other hand, if I knew that the fateful bear attack wouldn't come until I was 120, then I could take appropriate steps so that I had enough money to last me seventy years.

But I don't know when and how I'll die. Neither do you. As a result, the best we can do is guess how long we'll live and how much money we'll need.

Very few people regret saving money. In fact, these researchers found that only 1.7% of respondents would have saved less if they could re-do their earlier life.

While 66.6% of respondents wished they had saved more when they were younger, about 10% of these folks say they could not have done so. There wasn't any way they could have spent less. But that means 60.9% of those surveyed could have and should have increased their saving rate.

What do people wish they'd spent less on? Men wish they had spent less on cars. Women wish they had spent less on clothing. And as much as it pains me, everyone wishes they had spent less on vacation. I sure hope my own travel spending doesn't come back to haunt me later in life.

Poorer people have greater saving regret. The authors write: “Among those in the highest wealth quartile, 38.9 percent expressed saving regret; among those in the lowest wealth quartile, 71.9 percent did so.”

It's tough to trace cause and effect here, of course, but I don't think it matters. The message is clear. The poorer your personal economic situation, the more important it is for you to save!

Wading through the jargon, there's a lot of interesting stuff about aging and aging in this paper. I've touched only on the main points. Some of the background info and asides are equally fascinating. (How do researchers predict how people will make future decisions? How do they model saving habits? What do they think of self-determination?)

But the bottom line is obvious: To avoid regrets when you're older, save more now.

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)

![This graphic by James Clear shows the Mr. Money Mustache version of Stephen Covey's circles. Confused? I don't blame you! [Circle of Concern vs. Circle of Control]](https://www.getrichslowly.org/wp-content/uploads/23783342876_61fe34d89c.jpg)