Why don’t Americans save?

A new report from the Center for Financial Services Innovation says that only 28% of Americans are financially healthy. And it reinforces something we already knew: The U.S. saving rate sucks. Americans don't save.

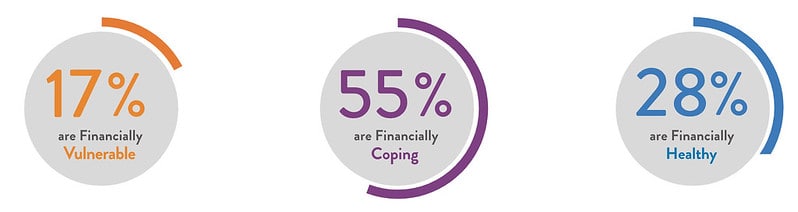

The U.S. Financial Health Pulse divides people into three tiers of financial health.

- Financially healthy people (28% of the U.S., 70 million people) are “spending saving, borrowing, and planning in a way that will allow them to be resilient and pursue opportunities over time.”

- Financially coping people (55%, 138 million) are “struggling with some, but not necessarily all, aspects of their financial lives.”

- Financially vulnerable people (17%, 42 million) are “struggling with all, or nearly all, aspects of their financial lives.”

The full report is huge — it's an 80-page PDF! — and filled with data based on survey responses from 5000 people. The document does a great job of presenting the info, separating it into four major sections (spend, save, borrow, plan), then comparing how people in each financial health tier differ in their approaches.

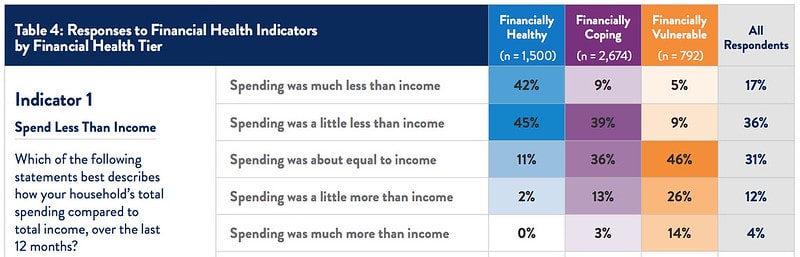

Here, for instance, are the results for the survey question about saving rate:

In the nearly thirteen years I've been writing Get Rich Slowly, I've seen reports like this over and over and over again. It's a constant refrain: American's don't save. But why don't they save?

The U.S. Saving Rate

There's a tendency in some circles to blame outside forces for our national inability to save. “People can't save because the economy sucks. Incomes are low and expenses are high.”

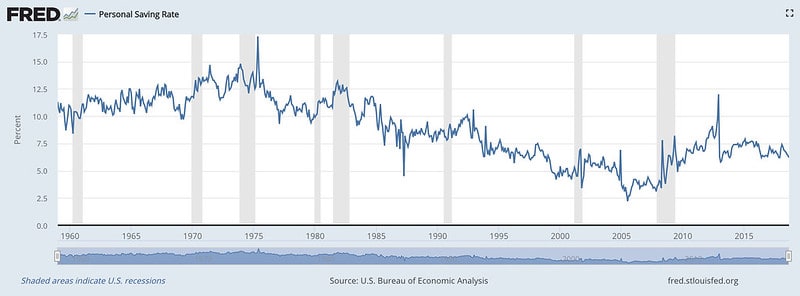

I'm not going to say that stagnating wages don't play a part in the problem, but I dont think they're a primary factor. In fact, if you look at a chart of the U.S. saving rate over time, you can see a surprising pattern. (This data comes from the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.)

See those grey shaded areas in the chart above? Those are recessions. When the economy is bad, people tend to save more. When the economy is booming — the mid 1980s, the late 1990s, the mid 2000s, now — people save less. This takes the teeth out of the whole “people can't save because of the economy” argument.

I think the problem with the American saving rate is complex. There are many forces working together to depress saving rates in this country.

Why Don't Americans Save?

Many writers and pundits have tried to tackle this topic over the past twenty years. I feel like most of the analysis is facile and/or guided by a political agenda. Deep thought on the subject — such as this fine article from The Atlantic — is rare.

In that Atlantic article from 2016, author Derek Thompson explores five different theories, examining the pros and cons of each. Thompson says these five factors are each a piece of the problem:

- Americans stopped saving when their incomes stopped growing. (Like me, he finds this argument incomplete and/or unconvincing.)

- The poor and middle class went into debt to buy houses. There is a clear correlation between increased homeownership and decreased saving.

- U.S. policies make it easy to not save money. It's too easy to access our retirement accounts, pulling out money we oughtn't pull out.

- The U.S. is uniquely susceptible to conspicuous consumption. This is a subject I've been discussing with folks by email lately. Look for future articles about “identity economics“.

- The pressure to keep up with richer neighbors has been greatly exacerbated by rising income inequality.

Thompson doesn't believe any single factor is wholly to blame. He thinks it's a combination of these things. (He and I also agree that anyone at any income level is capable of saving. He writes: “The poor can save more money, and it’s not offensive to suggest so.” Preach!)

In addition to Thompson's five factors, I'd propose three other possible reasons Americans don't save.

- We're not encouraged to save. There's a vast, sophisticated advertising industry designed to separate people from their money. Nobody believes ads work on them, yet they're working on somebody! Otherwise companies wouldn't pump hundreds of billions into advertising each year. (Trust me: Ads affect you.) But there are precious few ads encouraging us to spend less and save more.

- We're not clear on what we want to use our money for. Here at Get Rich Slowly, I'm adamant that readers need to find their purpose in life. You need some vague idea of where you're headed, at the very least. Without a vision of the future, you can't make smart choices about your money in the present. Spending on one thing is as good as spending on another. With a destination in mind, it's easy to know when your spending undermines your long-term goals.

- We're taught that money is complicated. It's not. The basic math of money is shockingly simple. It's the psychology and behavior that's difficult to master. There's another vast industry of financial advisors with a vested interest in convincing you that this stuff is difficult and that you must have help. More people need to know that yes, they can manage their own money effectively.

Looking back at that chart of how the U.S. saving rate has changed over time, I also wonder if some of the patterns can be attributed to the forever fallacy. When times are bad, we believe they'll always be bad, so we save more. When times are good, we tend to believe they'll always be good, so we spend more.

Solving the Problem

It's one thing to point out that there's a problem — a problem we're all aware of — but it's something else entirely to provide solutions.

In his Atlantic article, Thompson advocates government-level changes: banning lotteries, expanding Social Security, limiting withdrawals from retirement accounts. Perhaps these measures would be effective, but I'm not a fan of looking for societal solutions to personal problems. (Remember: I believe that becoming proactive is the number-one secret to wealth, freedom, and happiness.)

Other folks I admire are proponents of greater financial education. They want personal finance classes in high schools and/or increased financial literacy education for adults. The Plutus Foundation, for instance, is working hard to increase financial literacy by funding a variety of community-based programs.

From my experience, the trouble is that financial literacy fails more often than not. Most programs are targeted at teaching math and mechanics; they ignore behavior. It's not the math and mechanics that are the issue! Until we turn our attention from traditional financial literacy to something else — behavioral literacy? — these programs will remain ineffective.

So, what's the solution? I wish I had one.

Personally, my answer is to continue providing solid money advice for those actively hunting for help. My goal is to make Get Rich Slowly a treasure trove of information for those who stumble upon it. (Testimonials from readers like you seem to indicate I'm meeting my aim!)

Lately, the GRS team and I have been talking a lot about who this site is for. Conventional wisdom is that in order to be successful, a site has to be laser-focused on a specific audience. Get Rich Slowly is not laser-focused…and I don't want it to be. I want this to be a place for everyone to get help with money.

Yesterday, as I was massaging some old Money Boss material into the archives here at GRS, it occurred to me that perhaps I do have an answer to these two problems: Why don't Americans save? What audience is GRS for?

At Money Boss, my goal was to get people to manage their household finances as if they were managing a small business. Everybody understands that a business needs to earn a profit in order to survive and thrive, but few realize the same applies their personal lives. “Profit” for a business is the same as “savings” for an individual.

What if I took this metaphor, a metaphor that I thought I was going to retire, and used it to provide editorial direction at Get Rich Slowly? What if I tried to promote this as widely as possible, to in some small way encourage Americans to save more?

That's exactly what I intend to do. My mission in life is to help as many people as possible learn to manage their money so they can earn a “personal profit”. I want them to use this profit to fund whatever their personal mission happens to be.

I can't change the habits of an entire country. But, one person at a time, I can help a handful of people learn to save.

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)