The perfect is the enemy of the good

I’m home! Over the past two weeks, I drove 1625 miles across across seven southeastern states. I had a blast hanging out with readers, friends, and colleagues. Plus, it was fun to explore some parts of the country that Kim and I skipped during our RV trip a few years ago. Most fun of all, though, was talking to dozens of different people about money.

After two weeks of money talk, I have a lot to think about. I was struck, for instance, by how many people are paralyzed by the need to make perfect decisions. They’re afraid of making mistakes with their money, so instead of moving forward, they freeze — like a deer in headlights.

It might seem strange to claim that the pursuit of perfection prevents people from achieving their financial aims, but it’s true. Long-time readers know that this is a key part of my financial philosophy: The perfect is the enemy of the good.

Here, for instance, is a typical reader email:

Thirty-plus years ago I was making much less money than when I retired so my tax rate was lower. I sometimes wonder now if it would have been better to pay the taxes at the time I earned the money and invest and pay taxes all along rather than deferring the taxes. You can make yourself crazy thinking about stuff like that!

Yes, you can make yourself crazy thinking about stuff like that. This reader retired early and has zero debt. They’re in great financial shape. Yet they’re fretting over the fact that tax-deferred investments might not have been the optimal choice back in 1986.

Regret is one of the perils of perfectionism. There are others. Let’s look at why so many smart people find themselves fighting the urge to be perfect.

Maximizers and Satisficers

For a long time, I was a perfectionist. When I had to make a decision, I only wanted to choose the best. At the same time, I was a deeply unhappy man who never got anything done. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, the pursuit of perfection was the root of my problems.

In 2005, I read The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz. This fascinating book explores how a culture of abundance actually robs us of satisfaction. We believe more options will make us happier, but the increased choice actually has the opposite effect. Especially for perfectionists.

Schwartz divides the world into two types of people: maximizers and satisficers. Here’s how he describes the difference:

Choosing wisely begins with developing a clear understanding of your goals. And the first choice you must make is between the goal of choosing the absolute best and choosing something that is good enough. If you seek and accept only the best, you are a maximizer…Maximizers need to be assured that every purchase or decision was the best that could be made.

In other words, maximizers are perfectionists.

“The alternative to maximizing is to be a satisficer,” writes Schwartz. “To satisfice is to settle for something that is good enough and not worry about the possibility that there might be something better.“

To maximizers, this sounds like heresy. Settle for good enough? “Good enough seldom is!” proclaims the perfectionist. To her, the satisficer seems to lack standards. But that’s not true.

A satisficer does have standards, and they’re often clearly defined. The difference is that a satisficer is content with excellent while a maximizer is on a quest for perfect.

And here’s the interesting thing: All of this maximizing in pursuit of perfection actually leads to less satisfaction and happiness, not more. Here’s what Schwartz says about his research:

People with high maximization [tendencies] experienced less satisfaction with life, were less optimistic, and were more depressed than people with low maximization [tendencies]…Maximizers are much more susceptible than satisficers to all forms of regret.

Schwartz is careful to note that being a maximizer is correlated with unhappiness; there’s no evidence of a causal relationship. Still, it seems safe to assume that there is a connection.

I’ve seen it in my own life.

Maximizing in Real Life

In the olden days, for instance, if I needed to buy a dishwasher, I would make an elaborate spreadsheet to collate all of my options. I’d then consult the latest Consumer Reports buying guide, check Amazon reviews, and search for other resources to help guide my decision. I’d enter all of the data into my spreadsheet, then try to find the best option.

The trouble? There was rarely one best option for any choice I was trying to make. One dishwasher might use less energy while another produced cleaner dishes. This dishwasher might have special wine holders while that had the highest reliability scores. How was I supposed to find the perfect machine? Why couldn’t one manufacturer combine everything into one Super Dishwasher?

It was an impossible quest, and I know that now.

Nowadays, I’m mostly able to ignore my maximizing tendencies. I’ve taught myself to be a satisficer. When I had to replace my dead dishwasher three years ago, I didn’t aim for perfection. Instead, I made a plan and stuck to it.

- First, I set a budget. Because it would cost about $700 to repair our old dishwasher, I allowed myself that much for a new appliance.

- Next, I picked one store and shopped from its universe of available dishwashers.

- After that, I limited myself to only a handful of brands, the ones whose quality I trusted most.

- Finally, I gave myself a time limit. Instead of spending days trying to find the Best Dishwasher Ever, I allocated a couple of hours on a weekend afternoon to find an acceptable model.

Armed with my Consumer Reports buying guide (and my phone so that I could look stuff up online), I marched into the local Sears outlet center. In less than an hour, I had narrowed my options from thirty dishwashers to three. With Kim’s help, I picked a winner.

The process was quick and easy. The dishwasher has served us well for the past three years, and I’ve had zero buyer’s remorse.

A Trivial Example

At Camp FI in January, one of the attendees explained that he’s found freedom through letting go of trivial decisions. For things that won’t have a lasting impact on his life, he doesn’t belabor his options. Instead, he makes a quick decision and moves on.In restaurants, for instance, he doesn’t look at every item on the menu. He doesn’t try to optimize his order. Instead, he makes a quick pass through the list, then picks the first thing that catches his eye. “It sounds silly,” he told me, “but doing this makes a huge difference to my happiness.”

For the past four months, I’ve been trying this technique. You know what? It works! I now make menu choices in seconds rather than minutes, and my dining experience is better because of it. This is a trivial example, I know, but it’s also illustrative of the point I’m trying to make.

Perfect Procrastinators

Studies have shown that perfectionists are more likely to have physical and mental problems than those who are open-minded and flexible. There’s another drawback to the pursuit of perfect: It costs time — and lots of it. To find the best option, whether it’s the top dishwasher or the ideal index fund, can take days or weeks or months. (And sometimes it’s an impossible mission.)

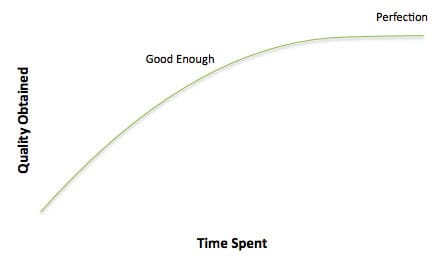

The pursuit of perfection is an exercise in diminishing returns:

- A bit of initial research is usually enough to glean the basics needed to make a smart decision.

- A little additional research is enough to help you separate the wheat from the chaff.

- A moderate amount of time brings you to the point where you can make an informed decision and obtain quality results.

- Theoretically, if you had unlimited time, you might find the perfect option.

The more time you spend on research, the better your results are likely to be. But each unit of time you spend in search of higher quality offers less reward than the unit of time before.

Quality is important. You should absolutely take time to research your investment and buying decisions. But remember that perfect is a moving target, one that’s almost impossible to hit. It’s usually better to shoot for “good enough” today than to aim for a perfect decision next week.

Procrastination is one common consequence of pursuing perfection: You can come up with all sorts of reasons to put off establishing an emergency fund, to put off cutting up your credit cards, to put off starting a retirement account. But most of the time, your best choice is to start now.

Who cares if you don’t find the best interest rate? Who cares if you don’t find the best mutual fund? You’ve found some good ones, right? Pick one. Get in the game. Just start. Starting plays a greater role in your success than any other factor. There will always be time to optimize in the future.

When you spend so much time looking for the “best” choice that you never actually do anything, you’re sabotaging yourself. The perfect is the enemy of the good.

Final Thoughts

If your quest for the best is making you unhappy, then it’s hurting rather than helping. If your desire to get things exactly right is preventing you from taking any sort of positive action, then you’re better off settling for “good enough”. If you experience regret because you didn’t make an optimal choice in the past, force yourself to look at the sunny side of your decision.

- Train yourself to be a satisficer. Ask yourself what “good enough” would mean each time you’re faced with a decision. What would it mean to accept that instead of perfection?

- If you must pursue perfection, focus on the big stuff first. I get a lot of email from readers who fall into the optimization trap. They spend too much time and energy perfecting small, unimportant things — newspaper subscriptions, online savings accounts, etc. — instead of the things that matter most, such as housing and transportation costs. Fix the broken things first, then optimize the big stuff. After all of that is done, then it makes sense to get the small things perfect.

- Practice refinement. Start with “good enough”, then make incremental improvements over time. Say you’re looking for a new credit card. Instead of spending hours searching for the best option, find a good option and go with it. Then, in the months and years ahead, keep an eye out for better cards. When you find one you like, make the switch. Make perfection a long-term project.

- Don’t dwell on the past. If you’ve made mistakes, learn from them and move on. If you’ve made good but imperfect decisions — such as the Money Boss reader who wishes they hadn’t saved so much in tax-deferred accounts — celebrate what you did right instead of dwelling on the minor flaws in the results.

- Embrace the imperfection. Everyone makes mistakes — even billionaires like Warren Buffett. Don’t let one slip-up drag you down. One key difference between those who succeed and those who don’t is the ability to recover from a setback and keep marching toward a goal. Use failures to learn what not to do next time.

I don’t think perfection is a bad thing. It’s a noble goal. It’s not wrong to want the best for yourself and your family. But I think it’s important to recognize when the pursuit of perfection stands in your way rather than helps you build a better life.

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)