Financial freedom and the value of time

Note from J.D.

Last October, I had a chance to read an advance copy of Grant Sabatier‘s new book, Financial Freedom, which was just released this morning. I liked it. I loved parts of it. In fact, the second chapter of Financial Freedom inspired my article about how time is more valuable than money.Today, I'm pleased to present a (heavily edited) excerpt from that second chapter. Here's Sabatier on why time is more valuable than money — and why you can and should retire early. (Links and photos are from me. Everything else is from the book. Note, however, I've heavily edited this chapter in order to abridge it and to make it more readable in blog format.)

If some ninety-year-old rich dude offered you $100 million to trade places with him, would you do it? Of course not. Why? Because time is more valuable than money.

The average person has approximately 25,000 days to live in their adult life. If you’re reading this, you likely need to trade your time for money in order to live a life that is safe, healthy, and happy. But if you didn’t have to work to make money, you’d be able to spend that time however you wanted.

No one cares about your time as much as you do. People will try to take your time and fill it up with meetings and calls and more meetings. But it’s your time. Your only time. Financial Freedom is designed to help you make the most of it. Make money buy time.

My goal is to help you retire as early as possible. When I say retire, I don’t mean that you'll never work again, only that you’ll have enough money so that you never have to work again. This is complete financial freedom — the ability to do whatever you want with your time.

Traditional Retirement Advice Doesn't Work

I don’t ever plan to retire in the traditional sense of the word, but you could say that I’m “retired” now because I have enough money and freedom to spend my time doing whatever I want. I no longer have to work for money, but I still enjoy making money, and it’s attached to many of the things I enjoy doing. I love working and challenging myself and hopefully always will, so checking out to a life of leisure just isn’t my vibe.

If you want to “retire” sooner rather than later, you need to rethink everything you’ve been taught about retirement and probably most of what you’ve been taught about money. As a society, we have collectively adopted one approach to retiring: get a job, set aside a certain portion of your income in a 401(k) or other retirement account, and in 40+ years you’ll have enough money saved that you can stop working for good.

This approach is designed to get you to retire in your sixties or seventies, which explains why pretty much every advertisement about retirement shows silver-haired grandmas and grandpas (typically on a golf course or walking along the beach).

There are three major problems with this approach:

- It doesn’t work for most people.

- You end up spending the most valuable years of your life working for money.

- It’s not designed to help you “retire” as quickly as possible.

The first major problem with traditional retirement advice is that even if you follow it perfectly (and most people usually don’t), you still might not have enough to live on when you are in your sixties.

The popular advice to save 5% to 10% of your income isn't enough. You should be saving as much money as early and often as you can. If you want to be sure you'll be able to retire at 65, you need to start (and keep) saving at least 20% of your income from the age of 30.

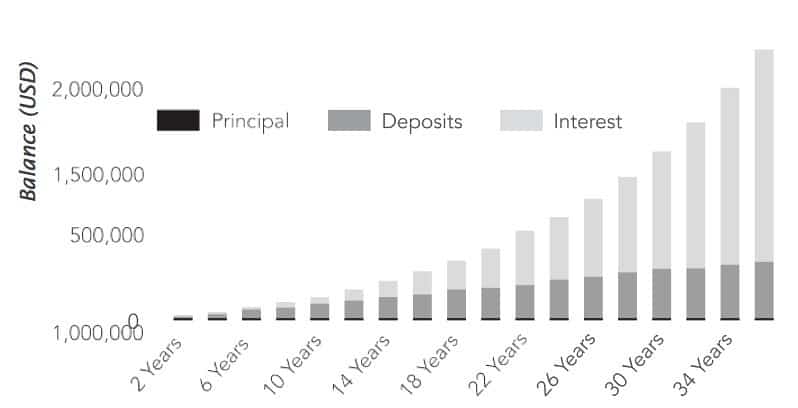

Here’s how big a difference it makes.

If you're making an average of $50,000 over this 35-year period and saving 20%, or approximately $10,000 per year, you’d have deposited $349,860 by the time you retire. Factoring in the 7% growth rate adjusted for inflation, that investment would be worth $1,615,340.

And this is assuming that your salary never increases, which it very likely would over time, so you'll have even more money.

Saving 20% of your income will significantly increase the chance that you can retire after 40 years. But this brings us to the second and third major problems with traditional money advice: It isn't designed to help you “retire” early and requires you to work full time between your twenties and your sixties.

There's nothing inherently wrong with this, and people can live perfectly happy lives working for 40 years and then enjoying the fruits of their labor when they’re older. But it requires a huge trade-off — basing 40 years of your life around earning money — and the payoff isn't guaranteed.

A Dream Deferred

All my life, I grew up around people who worked and hoped they could retire one day.

Neither of my parents come from money, and I knew growing up that we didn’t have a lot of money. We weren’t poor by any stretch, but given that we lived outside of Washington, D.C., surrounded by some of the wealthiest suburbs in America, my parents lived a frugal lifestyle. My parents bought used cars, we took an annual beach vacation, and we drove twelve hours each way to spend holidays in Indiana.

Despite our East Coast address, my parents retained their Midwestern values. I was consistently exposed to the classic American work ethic: get a job, pay your dues, save wisely, and if you play your cards right, you can retire sometime in your golden years. Everyone I knew worked well into their sixties, if not longer. My grandparents worked well into their seventies because they couldn’t afford to retire earlier than that.

Both of my parents are in their sixties and still working. They probably have enough money to retire, but they worry it might not be enough in the long run. They also both wonder what they would do with their time if they did retire.

When you spend almost your entire life working for a paycheck, what happens when you break that routine? What happens when your identity is wrapped up in your title and job responsibilities? What happens when you’re now too tired to pursue your dreams, or maybe it’s been so long that you lost your dreams along the way?

My dad recently told me about a few of his neighbors who had retired after 40 years in the workforce. “They spend a lot of their time in their yards picking up sticks,” he said. I don’t know these people, but I can’t imagine this is what they hoped they’d be doing in the twilight of their lives.

This illustrates a common problem with the typical approach to retirement that few people consider: Despite the fact that they work so hard to be able to retire, 48% of Americans over 55 haven’t even thought about what they want to do when/if they retire.

I don’t know about you, but this makes me pretty sad, because it means many Americans are choosing to work for several decades of their lives without giving any thought to what they’re working toward. They have collectively adopted the traditional retirement narrative — work until your sixties or seventies — without pausing to question whether this is what they really want out of life or if there’s a better way.

A New Perspective

In her deeply moving book The Top Five Regrets of the Dying, nurse Bronnie Ware says the top two regrets of those facing the end of their lives are “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me,” and “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.”

She goes on to say that the vast majority of her patients never accomplished at least half of their dreams, often because of their choice to keep working instead of following them. These people pushed on, saved, and worked only to look back and wonder what it was all for.

Is this what you want? Do you want to defer your dreams until sometime in the far-off future when you might not have the energy or drive to do anything but pick up sticks all day?

It was only after I started my quest to save $1 million as quickly as possible that I started to notice the limits to typical financial advice and the traditional retirement narrative. As I learned more about how to earn, save, and invest money, I realized that making money quickly isn't nearly as complicated as it’s made out to be. In fact, given the efficiencies of the internet, it’s easier to do than ever before.

What's difficult is letting go of the assumption that there's only one surefire path to retirement — earning a steady paycheck for several decades and saving a portion of it for later — and that any other path is reserved for the lucky few.

The more money you make, the more money you can invest, and the faster you'll reach financial freedom.

Caveat

It’s important to note that there are some limits, and being able to “retire” early is definitely a privilege that not everyone has or will have.There are millions of people in the United States who are simply trying to keep a roof over their heads and buy food to feed their families. If you're making less than $25,000 per year, then it will be a lot harder to retire early because you simply won’t be able to save as much as someone earning a higher income. (Unless, of course, you can live on $5,000 a year, like the happy wanderer I met in Flagstaff, Arizona.) I’m not saying it isn’t possible; it will just require a lot of creativity and sacrifice.

The hardest part of fast-tracking financial freedom is learning to look at the world differently, to accept that even though you may not know a single person who has done it, it's possible to earn enough so that within just a few years, you'll never have to worry about money again.

But if you want to live life on your terms, you need to manage money on your own terms as well, and that requires a new perspective.

Time vs. Money

One of the main reasons traditional retirement and personal finance advice is so limiting is because it's based on the false assumption that money is limited. The vast majority of personal finance advice out there is focused on cutting back and spending less and doesn’t acknowledge the simple truth that money is limited only if you don’t try to make more of it.

Money is inherently infinite.

It’s a human invention, and as long as people are helping the economy grow by working, spending, and investing, governments can print more money to keep up. Yes, there is and always has been a massive gap between those who have a lot of money and those who don’t, and billions of people live in places where they don’t have the moneymaking opportunities that those of us in democratic, capitalist societies have.

But, in theory, there's enough money in the world for everyone to have all the money they need.

The problem is, many people don’t take advantage of these opportunities and instead accept whatever money they are given — generally whatever their bosses are willing to pay — without considering other ways to make more money. They say they want to make more money but spend all their free time binging on Netflix, gaming, or just wasting time.

This is too bad, because when we believe that money is scarce, we end up sacrificing a great deal of time in order to make and save it. And unlike money, time is inherently limited.

In one of my favorite books, Your Money or Your Life, author Vicki Robin asks us to ponder a simple but transcendent question: What are the hours of your life worth? What are you willing to trade them for? How much money are you willing to trade for your time?

If we believe money is scarce, we'll spend precious time trying to save it when we actually don’t have to. We’ll spend hours clipping coupons, driving an extra mile to save three cents a gallon on gas, or hunting for a deal online just to shave a few bucks off our bill.

I once spent over four hours looking for the best deal on a new TV. It was only later that I considered that the money I’d saved hardly made up for the time I’d wasted — time that I'll never get back.

The same goes for earning money. Every minute we spend trying to make money is a minute we can’t use to do something else — it’s gone forever.

Trading Time for Money

Most people work between 70,000 and 80,000 hours over the course of their careers, but even that doesn’t account for all the time they spend because they have to work. The average American commutes 52 minutes to and from work each day. That’s about 8,700 hours over the course of a typical career. All told, you’re trading time for money — spending more than a year of your life doing something you wouldn’t have to do if you didn’t have to earn money to survive.

Even these stark numbers don’t tell the whole story.

The average American works 34.4 hours a week. If we add in time for commuting, that’s about 38.7 hours. There are 168 hours in a week, so after you subtract about 56 hours for sleeping, that leaves 73.3 hours.

That sounds like a lot — more than double what you spend working in a week — but consider that not all hours are created equal. Studies have shown that we're most alert and energetic early in the day, but that’s the time we’re usually working. By the time we get off the clock, we’re usually so tired or run-down from working all day and commuting that we don’t want to do anything except sit on the couch. This is why the average American watches 5.4 hours of TV a day.

Sure, we have weekends, but how often do you spend those running around trying to catch up on all the errands and chores you didn’t get to during the week?

I’m not anti-work; in fact, I like working. Humans need to work to be happy. But like time, not all work is created equal. There's a huge difference between working at a job you hate, being stuck at a desk or on the clock for 40 or more hours a week, and doing work you love and are passionate about, on your own time, and having the freedom to do something else if you want to.

The same trade-off occurs when you look at your life as a whole. You typically have more energy and are healthier in your twenties, thirties, and forties than you are later in life. But if you have to spend those decades working for money, then you’re not taking full advantage of this time.

From a financial standpoint, if you gradually save a small percentage of your income over the course of 40+ years, you’re wasting time that your money could use to grow. When you invest money in the stock market, it grows in value over time because (on average over the long term) it earns returns every year. If you’re saving only 5% to 10% of your annual income each year over the course of several decades, you’re not giving your money nearly as much opportunity to compound as you would if you invested more earlier in your life.

You're wasting time.

Don’t waste time. You are in control. Remember, it’s your time. If you take advantage of opportunities to make more and make the most of your money, you can save a lot more money and correspondingly even more time. Every $1 invested today is worth hours, if not days, of your freedom in the future. The more you save today, the more time you buy in the future.

Time Is More Valuable Than Money

Fortunately, the relationship between money and time isn't strictly linear: If you want to make more money, you don’t necessarily need to sacrifice more time to do so. You don’t have to be limited by your own hours or even the hours in the day.

You don’t have to look far to find examples of people who can work half as many hours to earn twice as much money as someone else, and it’s not always because they're smarter or more experienced, or work in a more lucrative field. You can even find people who make money by trading very little, if any, of their own time because they’ve invested a lot of time up-front in building consistent long-term income streams.

Likewise, people who invest their money spend minimal time (other than what it takes to set up and manage their accounts) trying to make that money grow because as long as their money stays invested in the stock market, it will grow automatically over time. This is known as passive income because you don’t have to actively do anything to earn it, and it's the ultimate moneymaking strategy. What’s better than being able to make money doing literally nothing?

Once you reach the point where you no longer have to trade your time for money, you can choose to spend that time however you please. When you have enough (or even just close to enough!), you can quit the higher-paying job you hate to take a lower-paying one that's meaningful to you. You can explore, grow, give back, follow your passions, and find new passions. You can travel the world, pick up a new hobby, learn a new skill, volunteer — the possibilities are infinite.

- Anita retired at thirty-three so she could sleep in every day and travel the world without having to negotiate vacation days with her boss or worry about missing an important email.

- Sarah retired at thirty-two so she could learn to play the violin and start a band.

- Michelle did it at twenty-eight so she could live in an RV, travel the country, and blog full time.

- Justin did it so he could sit in a hammock at eleven a.m. on a Tuesday and read a good book.

- Kristy and Bryce did it at thirty-one and thirty-two, respectively, so they could travel the world on a whim.

- J.P. did it so she could walk her dog in the middle of the day, discover new passions, and raise a family.

- Brandon retired at thirty-four so he could spend his time making music and exploring new passions.

I retired early because I didn’t want to spend the best years of my life working in a poorly lit cubicle at a stressful job I didn’t particularly enjoy. And because I did it, I had the time to write Financial Freedom and teach others how to escape the rat race.

The vast majority of personal finance advice out there is focused on helping you maximize whatever limited money you already have. It’s focused on frugality, scarcity, cutting back, and spending less, and doesn’t acknowledge that money is limited only if you don’t try to make more.

Money is unlimited. Time is not. Don’t waste time. Don’t defer your dreams into the future.

Want to read more? Pick up a copy of the book or head on over to Sabatier's website, Millennial Money. Adapted from Financial Freedom by Grant Sabatier by arrangement with Avery, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © 2019, Grant Sabatier.

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)