How to set smart goals: What science says about getting what you want

During my two-week break, I've been working to migrate some of my old Money Boss articles to Get Rich Slowly. I thought this long piece on how to set good goals might be useful to those of you about to set goals and resolutions for 2018, so I'm publishing it today. Enjoy!

We've reached one of my favorite parts of the year: the transition from the old to the new. I like that so many of us pause during the winter to reflect on how are lives are going — and the direction we'd like them to head.

As part of this, many folks set goals and resolutions for the coming year. Unfortunately, most of these goals and resolutions are destined to remain nothing more than dreams. Why? Because most people don't know how to set good goals.

I want to change that.

Let's take some time today to explore what science says about how to set smart goals and resolutions. My hope is that by arming yourself with this knowledge, you'll still be pursuing your aims in April — instead of having relegated them to the realm of dreams.

How to Set Good Goals

If you ask most people how to set good goals, they'll tell you that goals should be SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timed. While this sounds great — and it's a methodology I've pushed in the past myself — there's no actual evidence that it works. (Maybe your research skills are better than mine; if you can find studies that show SMART goals are effective, please let me know.)

So what kind of goals are effective? In The How of Happiness, Sonja Lyubomirsky shares her summary of the studies into productive (and happy) goalsetting. “There is persuasive evidence that following your dreams is a critical ingredient of happiness,” she writes. And it matters which goals you pursue while following those dreams:

The pursuit of goals that are intrinsic, authentic, approach-oriented [which I'm describing as “positive” in this article], harmonious, activity-based, and flexible will deliver more happiness than the pursuit of goals that are extrinsic, inauthentic, avoidance-oriented [or negative], conflicting, circumstance-based, or rigid. This mouthful of words is based on decades of research.

Let's look at each of these qualities a little more closely. According to science, Lyubomirsky says, the best goals will be:

- Intrinsic. Good goals come from inside you, not from an outside source. You'll be much more motivated to get things done if you're acting because you want to and not because you have to. Your goals should be things you'd do even if you weren’t required. (A bad goal is one you pursue simply to please others. Think “want” over “ought”.)

- Authentic. Lyubomirsky says that people are happier, healthier, and work harder when they choose goals aligned with their values. “The more a goal fits your personality, the more likely that its pursuit will be rewarding and pleasureful,” she writes. If you're an introvert, it might not make sense to make a resolution that involves joining a group. But if you have a dominant personality, a goal of getting involved in local government could be perfect.

- Positive. A good goal helps you pursue a desirable outcome instead of avoiding an undesirable one. What do I mean? Well, a resolution can usually be framed as an approach goal (e.g., to be fit) or an avoidance goal (e.g., not to be fat). Studies show that people who pursue avoidance goals are less happy and achieve worse results than those who pursue approach goals. So, find a way to state your aim in a positive way — as a target you're moving toward rather than something you're trying to escape.

- Harmonious. All of your goals should be aligned, complementing each other to create unified action. In this way, they can work together to make each one easier to achieve. Conflicting goals cause frustration and stress. (During my RV trip across the U.S., I had two goals that didn't work well together: I wanted to stay fit and I wanted to drink beer in every city I visited. You can guess how that turned out…)

- Flexible. Your goals will evolve over time. As your priorities change, your goals should too. Don't abandon difficult goals, but be willing to alter direction as your circumstances and priorities change.

- Activity-based. Goals that involve doing rather than getting tend to make people happier and more motivated. For one thing, you're likely to adapt quickly to whatever it is you achieve — whether it's moving to Miami or buying a new computer — so that the anticipated pleasure fades rapidly. Plus, you have more control over whether you do something than if you obtain something. For example, it's better to create a goal in which you aim to take 100 photographs per day (an action you can control) rather than one in which you aim to sell a photo to a national magazine (an outcome that may be beyond your reach).

That last bullet point is important and deserves additional clarification.

Remember how I've written in the past about developing an internal locus of control?

The first tenet of the Get Rich Slowly philosophy is: You are the boss of you. This means that you should spend time and money on the things that you can actually influence while ignoring those that you can't. When pursuing goals, I can't determine the results; I can only determine my effort. Thus, it makes sense to set goals based on my actions (write two hours per day, go to the gym five times a week, max out my Roth IRA) instead of desired outcomes (get 100,000 email subscribers, bench-press my bodyweight, earn a 10% return on my investments).

I think of it like this: It's better to prioritize habits over targets. You have more control over your input than you do over the outcomes.

Why go to all this trouble when setting goals? Because if you're careful to create good goals, you'll get better results — with your life and your finances. And the better your results, the more likely you'll be to continue working toward your goals…and your larger purpose.

Your Most Important Goals

Here's a quick exercise drawn from The How of Happiness.

Think about your current goals, the ones that are most important to your life today. “Goals” include intentions, wishes, dreams, and desires. On a piece of paper, list at least eight of your most meaningful goals. (You can list more than eight, but please list at least eight of your most important goals.)

Now you're going to evaluate each of your goals individually. Go through them one by one and ask yourself:

-

- Is the goal intrinsic or extrinsic? Are you doing it because

you

- want to, or because somebody else wants you to?

- Is the goal authentic or inauthentic? Does it feel like it fits you, or does it feel like it's not quite aligned with who you are?

- Is the goal positive or negative? Are you working toward a desired outcome, or are you trying to avoid something you don't want?

- Is the goal harmonious or conflicting? Does the objective work well with the other goals you've listed (and your overall purpose), or does it make your other aims more difficult to achieve?

- Is the goal flexible or rigid? If your life circumstances were to change, would the goal be easy to set aside, or does it create some sort of barrier to making future changes?

- Is the goal activity-based or circumstance-based? Is it based around doing something, or is it based around getting/achieving something?

In answering these questions, good goals will have more of the qualities listed first than the ones listed second. Great goals will have all six of the attributes that science says lead to happiness; they'll be intrinsic, authentic, positive, harmonious, flexible, and activity-oriented.

If your goals don't align well with Lyubomirsky's guidelines, ask yourself why this might be the case. Are there any discernible patterns? Are many of your goals extrinsic, based on what others want you to do? Are they avoidance goals, designed to help you keep away from some negative outcome? If there are patterns, what can you do to change them?

Next, let's look at the relative importance of goals. Not all goals are created equal!

A Hierarchy of Goals

In the past, I divided my goals based on how long it took to complete them: short-term goals, intermediate goals, and long-term goals. More and more, however, I've begun to think of my goals as existing in a hierarchy. Some goals are more important than others.

High-level goals aren't always long-term goals. Next week, for example, I'll start a two-week “cleanse” diet. This objective is high on my personal goal hierarchy, but it's also an immediate aim. And there are times when I have a long-term goal that's low on the goal hierarchy. I want to visit Antarctica, for instance, but I'm in no rush to do so. That's not a trip for which I need to be particularly fit, so it can wait until I'm older.

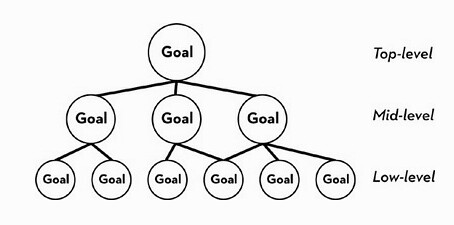

Perhaps the best explanation and exploration of goal hierarchies can be found in Angela Duckworth's Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. Here's a diagram from the book:

And here's how Duckworth describes it:

At the bottom of this hierarchy are our most concrete and specific goals — the tasks we have on our short-term to-do list: I want to get out the door today by eight a.m. I want to call my business partner back. I want to finish writing the email I started yesterday. These low-level goals exist merely as means to ends. We want to accomplish them only because they get us something else we want.

In contrast, the higher the goal in this hierarchy, the more abstract, general, and important it is. The higher the goal, the more it's an end in itself, and the less it's merely a means to an end.

[…]The top-level goal is not a means to any other end. It is, instead, an end in itself. Some psychologists call this an “ultimate concern”. Myself, I think of this top-level goal as a compass that gives direction and meaning to all the goals below it.

Duckworth's research suggests that success in life comes from grit — passion and perseverance — which is all about “holding the same top-level goal for a very long time”.

It's easier to pursue your passion when you've taken time to thoughtfully develop a group of goals to support it. “The more unified, aligned, and coordinated our goal hierarchies are, the better,” Duckworth writes. (This goes along with Lyubomirsky's point that your goals should be harmonious with each other.)

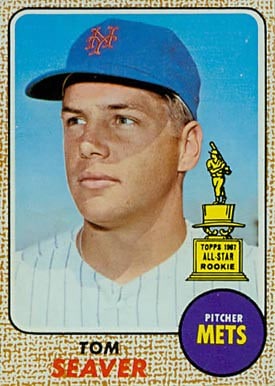

Duckworth, who likes to use athletes to illustrate her points, cites Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver as an example of somebody who built his life around a single mission, a mission that dictated his lower-level goals. In a 1972 interview with Sports Illustrated, Seaver stated his purpose clearly:

I've made up my mind what I want to do. I'm happy when I pitch well so I only do those things that help me be happy. I wouldn't be able to dedicate myself like this for money or glory, although they are certainly considerations. If I pitch well for 15 years I'll be able to give my family security. But that isn't what motivates me.

What motivates some pitchers is to be known as the fastest who ever lived. Some want to have the greatest season ever. All I want is to do the best I possibly can day after day, year after year. Pitching is the whole thing for me. I want to prove I'm the best ever.

And this purpose determined his day-to-day actions, his lower-level goals:

[Pitching] determines what I eat, when I go to bed, what I do when I'm awake. It determines how I spend my life when I'm not pitching.

- If it means I have to come to Florida and can't get tanned because I might get a burn that would keep me from throwing for a few days, then I never go shirtless in the sun.

- If it means when I get up in the morning I have to read the box scores to see who got two hits off Bill Singer last night instead of reading a novel, then I do it.

- If it means I have to remind myself to pet dogs with my left hand or throw logs on the fire with my left hand, then I do that, too.

- If it means in the winter I eat cottage cheese instead of chocolate chip cookies in order to keep my weight down, then I eat cottage cheese.

I might want those cookies but I won't ever eat them. That might bother some people but it doesn't bother me. I enjoy the cottage cheese. I enjoy it more than I would those cookies because I know it will help me do what makes me happy.

Obviously, not even the most successful people dedicate every waking moment to their purpose and passion. Everyone needs downtime. But ultimately your success will be determined by how well you build a hierarchy of goals that supports your purpose, then spend your time working to accomplish these objectives.

Your Goal Hierarchy

After reading Grit and seeing Duckworth's diagram, I spent some introspective time considering my own goals. Are they aligned with my purpose? Are they harmonious with each other? Are they intrinsic? In the end, I spent an hour or two on an exercise that I think could be useful to Get Rich Slowly readers.

Before you begin, you'll need to find space and time for introspective work where you won't be interrupted by people or pets or social media. You'll also need a pen and either a stack of index cards (or sticky notes) or a bunch of paper. You can't really do this project on a computer. (Maybe in a spreadsheet, but I think it's best on paper.)

Ready? Here's how it works.

- On your first index card, write down your mission statement, your purpose. (If you need help with this, here's a one-page PDF with an exercise meant to help you create your personal mission statement.)

- Next, write each of your top-level goals on its own index card (or sticky note or piece of paper). Clearly, if you haven't determine what your top-level goals are, you'll have to do so now. That's why you need space and time to think deeply! (As you come up with these goals, try to make sure they fit the profile for good goals I shared earlier in this article.) My top-level goals came naturally from my mission statement. One of them, for example, is “be the best person I can be, both mentally and physically”. Note that this is pretty vague. That's fine. Top-level goals tend to be vague. The lower you go, the more concrete your aims become.

- Now, for each of your top-level goals, make a list of supporting goals. Again, this might take some time. That's okay. When I did this, I came up with two goals to support my aim to “be the best person I can be, both mentally and physically”: (1) achieve and maintain physical fitness, and (2) achieve and maintain mental fitness.

- I think you can see where this is going. Your next step is to look at these new goals, and for each brainstorm a list of further supporting goals. When I took my goal to “achieve and maintain physical fitness”, for instance, I ended up with five sub-goals: eat well, drink only in moderation, exercise daily, practice good grooming, and dress well.

- Continue this process for each branch of the hierarchy until you reach the bottom. (The bottom might come at different levels in different places. Don't sweat it.) For my goal of “eat well”, I came up with four subgoals: keep portion sizes moderate, limit sugar intake, eat veggies first, and eat only when hungry. But for “dress well”, I only came up with two subgoals: maintain an attractive wardrobe, and wear nice clothes when possible.

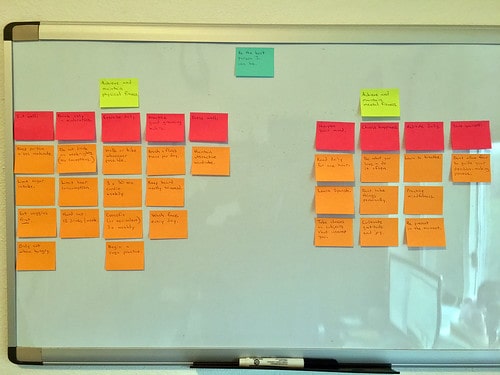

By the end of this exercise, my kitchen table was covered with sticky notes — over 100 of them. Because Kim would kill me if I left the table like that (and the cats would probably destroy the sticky notes), I moved them to a spare whiteboard where I highlighted the top-level goal that's most important to me right now (“be the best person I can be, both mentally and physically”). Here's a photo of what it looks like hanging in my office:

Good Goals in Action

When you set good goals, you can accomplish more than you might at first believe possible. After graduating from college, my friend Paula Pant decided she wanted to travel the world.

“I had a huge map of the world hanging up in my apartment,” Paula says. “I would just stare at it for hours thinking of all the places I wanted to go.” Because she wanted to travel, she made financial choices that others wouldn't.

“I hustled in the evenings and weekends writing freelance stories and increasing my income. I drove a $400 car, and I didn't even drive that much. I walked or biked pretty much anywhere I wanted to go,” says Paula. “And what's funny is that none of it actually felt like a sacrifice because I was so aware of the fact that these things were unimportant to me. It never felt like I was giving anything up.”

Paula's mission kept her motivated, and it helped her set appropriate goals. In 2008, she quit her job to spend two-and-a-half years traveling through Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. (She now writes about her financial philosophy at Afford Anything.)

Successful people have a purpose, and they set goals to help them progress toward their larger goal and mission. Paula's purpose was to explore the world, and that informed very decision she made. It helped her figure out which goals to pursue and which to ignore.

“Society says it's normal to have a nice apartment,” says Pant. “If that's what you dream about, if that's what keeps you awake at night, then go for it — if that's your dream. But if that's not really your passion, then slash it. Live in a dump so you can do what it is you love.”

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)