Is your home a better investment than the stock market?

I’ll admit it: There are times that I think everything that needs to be said about personal finance has been said already, that all of the information is out there just waiting for people to find it. The problem is solved.

Perhaps this is technically true, but now and then — as this morning — I’m reminded that teaching people about money is a never-ending process. There aren’t a lot of new topics to write about, that’s true (this is something that even famous professional financial journalists grouse about in private), but there are tons of new people to reach, people who have never been exposed to these ideas. And, more importantly, there’s a constant stream of new misinformation polluting the pool of smart advice. (Sometimes this misinformation is well-meaning; sometimes it’s not.)

Here’s an example. This morning, I read a piece at Slate by Felix Salmon called “The Millionaire’s Mortgage”. Salmon’s argument is simple: “Paying off your house is saving for retirement.”

Now, I don’t necessarily disagree with this basic premise. I too believe that money you pay toward your mortgage principle is, in effect, money you’ve saved, just as if you’d put it in the bank or invested in a mutual fund. Many financial advisers say the same thing: Money you put toward debt reduction is the same as money you’ve invested. (Obviously, they’re not exactly the same but they’re close enough.)

So, yes, paying off your home is saving for retirement. Or, more precisely, it’s building your net worth.

But aside from a sound basic premise, the rest of Salmon’s article boils down to bullshit.

Lying with Statistics

Looking past the “paying off your house is saving for retirement” subtitle on his piece (a subtitle that was likely added by an editor, not by Salmon), we get to his actual thesis: “Making mortgage payments can, in theory, be a way to accumulate wealth almost as effectively as contributing to a retirement fund.”

I’m glad Salmon qualified this statement with “in theory” and “almost” because this is pure unadulterated bullshit. And it’s dangerous bullshit. Here’s how this “logic” works:

If you buy an urban house today for $315,000 (the average price) and it appreciates at 8 percent a year for the next 15 years, you will be living in a $1 million house by the time you pay off your 15-year mortgage, and you will own it free and clear. Which is to say: You’ll be a millionaire.

For this to be true, here’s what has to happen.:

- Home prices in your area have to appreciate at an average of eight percent not just this year and next year, but for fifteen years.

- You have to take out a 15-year mortgage instead of a 30-year mortgage.

- You need to stay in that house (or continue to own it) for that entire fifteen years.

- Once you’ve become a millionaire homeowner, you now have to tap that equity for it to be of use. To do that, you have to sell your home, acquire a reverse mortgage, or otherwise creatively access the value locked in your home.

The real problem here, of course, are the assumptions about real estate returns. Salmon spouts huckster-level nonsense:

The 8 percent appreciation rate is aggressive, but not entirely unrealistic: It’s lower than the 8.3 percent appreciation rate from 2011 through 2017, and also lower than the 9 percent appreciation rate from 1996 to 2007.

That’s right. Salmon cites stats from 1996 to 2007, then 2011 to 2017 — and completely leaves out 2008 to 2010. WTF?

This as if I ran a marathon and told you that I averaged four minutes per mile…but I was only counting the miles during which I was running downhill! Or I told you that Get Rich Slowly earned $5000 per month…but I was only giving you the numbers from April. Or I logged my alcohol consumption for thirty days and told you I averaged three drinks per week…but left out how much I drank on weekends.

This isn’t how statistics work! You don’t get to cherry pick the data. You can’t just say, “Homes in some markets appreciated 9% annually from 1996 to 2007, then 8.3% annually from 2011 to 2017. Therefor, your home should increase in value an average of eight percent per year.” What about the gap years? What about the period before the (very short) 22 years you’re citing? What makes you think that the boom times for housing are going to continue?

Long-Term Home Price Appreciation

In May, I shared a brief history of U.S. homeownership. To write that article, I spent hours reading research papers and sorting through data. One key piece of that post was the info on U.S. housing prices.

Let me share that info again.

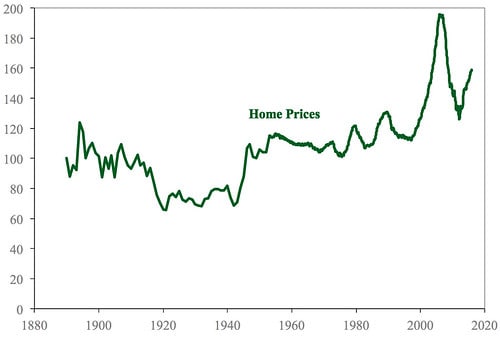

For 25 years, Yale economics professor Robert Shiller has tracked U.S. home prices. He monitors current prices, yes, but he’s also researched historical prices. He’s gathered all of this info into a spreadsheet, which he updates regularly and makes freely available on his website.

This graph of Shiller’s data (through January 2016) shows how housing prices have changed over time:

Shiller’s index is inflation-adjusted and based on sale prices of existing homes (not new construction). It uses 1890 as an arbitrary benchmark, which is assigned a value of 100. (To me, 110 looks like baseline normal. Maybe 1890 was a down year?)

As you can see, home prices bounced around until the mid 1910s, at which point they dropped sharply. This decline was due largely to new mass-production techniques, which lowered the cost of building a home. (For thirty years, you could order your home from Sears!) Prices didn’t recover until the conclusion of World War II and the coming of the G.I. Bill. From the 1950s until the mid-1990s, home prices hovered around 110 on the Shiller scale.

For the past twenty years, the U.S. housing market has been a wild ride. We experienced an enormous bubble (and its aftermath) during the late 2000s. It looks very much like we’re at the front end of another bubble today. As of December 2017, home prices were at about 170 on the Shiller scale. (Personally, I believe that once interest rates begin to rise again, home prices will decline.)

Here’s the reality of residential real estate: Generally speaking, home values increase at roughly the same (or slightly more) than inflation. I’ve noted in the past that gold provides a long-term real return of roughly 1%, meaning that it outpaces inflation by 1% over periods measured in decades. For myself, that’s the figure I use for home values too.

Crunching the Numbers

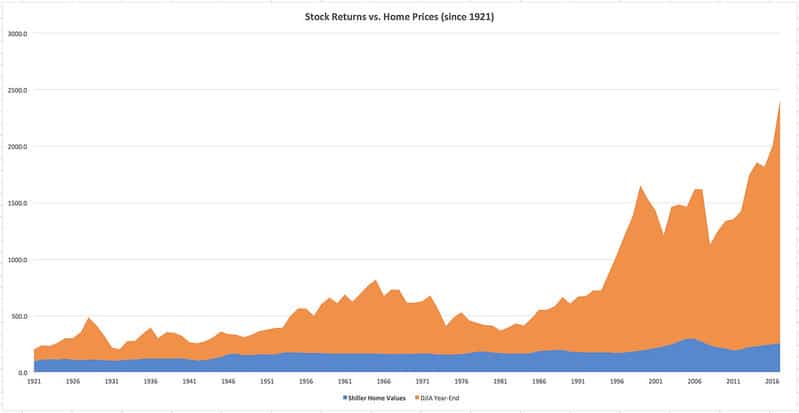

Because I’m a dedicated blogger (or dumb), I spent an hour building this chart for you folks. I took the afore-mentioned housing data from Robert Shiller’s spreadsheet and combined it with the inflation-adjusted closing value of the Dow Jones Industrial Average for each year since 1921. (I got the stock-market data here.) If you’d like, you can click the graph to see a larger version.

Let me explain what you’re seeing.

- First, I normalized everything to 1921. That means I set home values in 1921 to 100 and I set the closing Dow Jones Industrial Average to 100. From there, everything moves as normal relative to those values.

- Second, I’m not sure why but Excel stacked the graphs. (I’m not spreadsheet savvy enough to fix this.) They should both start at 100 in 1921, but instead the stock market graph starts at 200. This doesn’t really make much of a difference to my point, but it bugs me. There are a few places — 1932, 1947 — where the line for home values should actually overtake the line for the stock market, but you can’t tell that with the stacked graph.

As the chart shows, the stock market has vastly outperformed the housing market over the long term. There’s no contest. The blue housing portion of my chart is equivalent to the line in Shiller’s chart (from 1921 on, obviously).

Now, having said that, there are some things that I can see in my spreadsheet numbers that don’t show up in this graph.

Because Felix Salmon at Slate is using a 15-year window for his argument, I calculated 15-year changes for both home prices and stock prices. I’ll admit that the results surprised me. Generally speaking, the stock market does provide better returns than homeownership. However, in 30 of the 82 fifteen-year periods since 1921, housing provided better returns. (And in 14 of 67 thirty-year periods, housing was the winner.) I didn’t expect that.

In each of these cases, housing outperformed stocks after a market crash. During any 15-year period starting in 1926 and ending in 1939 (except 1932), for instance, housing was the better bet. Same with 1958 to 1973. In other words, if you were to buy only when the market is declining, housing is probably the best bet — if you’re making a lump-sum investment and not contributing right along.

Another thing the numbers show is that you’re much less likely to suffer long-term declines with housing than with the stock market. Sure, there are occasional periods where home prices will drop over fifteen or thirty years, but generally homes gradually grow in value over time.

The bottom line? I think it’s perfectly fair to call your home an investment, but it’s more like a store of value than a way to grow your wealth. And it’s nothing like investing in the U.S. stock market.

For more on this subject, see Michael Bluejay’s excellent articles: Long-term real estate appreciation in the U.S. and Buying a home is an investment.

Final Thoughts

Honestly, I probably would have ignored Salmon’s article if it weren’t for the attacks he makes on saving for retirement. Take a look at this:

If you’re the kind of person who can max out your 401(k) every year for 30 or 40 years straight — disciplined, frugal, and apparently immune to misfortune — then, well, congratulations on your great good luck, and I hope you’re at least a little bit embarrassed at how much of a tax break you’re getting compared to people who need government support much more than you do.

Holy cats! Salmon has just equated the discipline and frugality that readers like you exhibit with “good luck”, and simultaneously argued that you should be embarrassed for preparing for your future. He wants you to feel guilty because you’re being proactive to prepare for retirement. Instead of doing that, he wants you to buy into his bullshit “millionaire’s mortgage” plan.

This crosses the line from marginal advice to outright stupidity.

There’s an ongoing discussion in the Early Retirement community about whether or not you should include home equity when calculating how much you’ve saved for retirement. There are those who argue “absolutely not”, you should never consider home equity. (A few of these folks don’t even include home equity when computing their net worth, but that fundamentally misses the point of what net worth is.)

I come down on the other side. I think it’s fine — good, even — to include home equity when making retirement calculations. But when you do, you need to be aware that the money you have in your home is only accessible if you sell or use the home as collateral on a loan.

Regardless, I’ve never heard anyone in the community argue that you ought to use your home as your primary source of retirement saving instead of investing in mutual funds and/or rental rental properties. You know why? Because it’s a bad idea!

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)