Leverage, Luck, and Living Well: A Conversation with Financial Columnist Scott Burns

During the first week of July, I had the privilege to chat with financial author Scott Burns. What was intended to be a brief interview about his new book, Spend ’til the End [my review] lasted for nearly two hours. Burns was fascinating.

During the first week of July, I had the privilege to chat with financial author Scott Burns. What was intended to be a brief interview about his new book, Spend ’til the End [my review] lasted for nearly two hours. Burns was fascinating.

It has taken weeks to edit this conversation into something digestible for the web. It’s still quite long, but I hope it’s as interesting to you as it is to me.

J.D.

Can you give my readers a brief history of your background?

Scott

I got very curious about money just in the course of my childhood. The first ten years of my life, I lived and shared a rented room — at one point in a house without plumbing — with my single mother. By the time I graduated from high school, I was a millionaire’s stepson. My economic experience runs the gamut.

I started writing about personal finance because one night my first wife and I were going to a dinner party, and she said, “Scott, I’ve heard you explain the economics of buying a house as many times as I want to. Could you just write it up so you can hand it out?” We were all in our twenties — it was a time of real mobility. Everybody was buying a house and doing all kinds of things that were brand new.

I started writing about people and money then, and it was just a wonderful, natural event. I thought, “Wow. I was meant to do this.”

J.D.

You’ve been writing about personal finance for a long time now. I’m curious if you’ve noticed things that have changed since you’ve started. Is the advice that you were giving in the late 1960s still relevant today? And what sorts of changes have you seen over the past 40 years?

Scott

Unfortunately, it hasn’t changed enough, because the basic issues don’t change. And because people approach the economic issues in the same — and repeatedly wrong — way. Things haven’t changed and you still have the same kind of spread of information conveyance. You have wonderful writers like Andy Tobias. Andy can’t make anything complicated. He’s just a wonderful writer. I’ve envied him from the get-go.

J.D.

He has a great, personable approach. I like it.

Scott

Yes. He’s an easy read. He gets to the essentials very quickly, and he doesn’t try to complex it. Lots of people, they want to make things complicated, either because they want to make a living by making it complicated, or because they want to demonstrate how smart they are to others who don’t understand it.

The task of a personal finance writer is to write things in an non-intimidating way so that you can reach the broadest number of people without degrading your content. If you insist on dumbing down — the usual route used to degrade the content — and, that doesn’t work. What we need is to be as lucid as humanly possible, have some amount of levity so that people won’t feel that they’re being punished, and get people to say, “Oh, money! This is another tool for adaptation! This is another way that I can improve my life. This is another way that I can escape having a life that consists of a long series of unpleasant surprises.”

If you really start to look at the big difference between people who have mastered their economic lives, it’s that they have fewer unpleasant surprises in their lives. A lot of us, probably most human beings — I don’t know that you can get through your life without some amount of unpleasant surprises — but if you can at least eliminate the money unpleasant surprises, that’ll make you better prepared to deal with divorce and the other traumas that life holds.

J.D.

You were talking about how the personal finance advice really hasn’t changed that much over the past 40 years, and I know that’s something you’ve addressed in Spend ’til the End.

One thing that you didn’t talk much about in the book is the notion of behavioral economics, which I know has been around since the mid-70s at least. But it only seems to be gaining prominence over the past few years. I often say that managing money isn’t about understanding the numbers, because anyone can understand that if you spend more than you earn, you’re going to end up in debt. But managing money is more about managing yourself, managing your mind, because it’s your relationship with money…

Scott

Yes, it is, although I wouldn’t go as far as you just did, saying that everybody understands that you can’t spend more money than you earn.

Yes, it is, although I wouldn’t go as far as you just did, saying that everybody understands that you can’t spend more money than you earn.

As a matter of fact, I would say that that is one of the most favored American illusions. We’re witnessing it right now with the housing crisis. For all of my professional life, and beyond that, buying a house has been a way to consume and grow your personal wealth at the same time.

Back in the 1970s, I wrote a column for Vogue magazine that was about just that. You could buy a home in a vacation area where real estate was appreciating rapidly, and you would take money out of your income pocket, and you would pay for the bills of the house, but the money would magically reappear in the increased value of the house. And that’s exactly what happened with the house I owned on Cape Cod. I took money out of one pocket, but when I eventually sold it, I got back way more than I’d ever spent on the house or its mortgage. And that was what was behind thinking like that, which works some of the time…

J.D.

Sure. Careful use of leverage.

Scott

Careful use of leverage and steadfast faith in the ability of our politicians to create ever-increasing amounts of inflation. You just go with those articles of faith. You can do well, as long as you can make the payments. There are always people who think that they can get rich by borrowing. And you may happen to do better by borrowing, but you’re probably not going to get rich.

I had a life lesson in that. My stepfather was worth over a million dollars in the early 1960s. By the time he died, we were qualifying for Medicaid, because he believed that no dollar should go unborrowed. He was unfailingly generous with all of his boys, including me, but he was a high roller. He would buy whatever and then trust that it would work out. Well, it didn’t work out.

J.D.

To me, this is a real philosophical difference that I encounter in my reading. On one end of the spectrum you have people like Dave Ramsey, who talk about how all debt is bad and you shouldn’t carry any debt. And on the other end of the spectrum you have people like Robert Kiyosaki who argues that debt lets you leverage and buy more than you would be able to otherwise, and that you should have as much leverage as you possibly can afford.

I tend to side more with the “no debt” people, but I can understand the use of some leverage. Obviously buying a house is an excellent example — at least, if you’re not buying too much house.

Scott

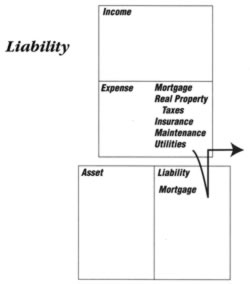

There’s only one useful thing that Robert Kiyosaki has ever written. In one of his early books, he has a quadrant, and he divides assets up into consuming assets and earning assets.

What you and I are talking about is the illusion of wealth that people get and the satisfaction that they get thinking, “Well, I’ve invested in my home, and it’s going to make me rich.” It will make them feel rich, but it isn’t what all of us eventually need, which is a large portfolio of earning assets. The house is a consuming asset, and the only way you might benefit from its appreciation is by selling it. So, that’s a very useful thing. But then, [Kiyosaki] takes that to the furthest extreme by saying you borrow as much money as possible to buy earning assets. Well, it don’t always work!

J.D.

And often you have to be able to borrow far more than the average person can afford. I read and reviewed his most recent book, and his examples drove me crazy. He’s talking about borrowing money to purchase a $17 million dollar apartment complex. Well, that’s fine if you can afford to borrow $17 million dollars, but I’m an average guy. I can’t afford that. What can I borrow to…

Scott

Yeah, but you could afford it if you had $3.4 million of debt.

J.D.

Exactly! I feel like his advice is often lacking practical application for the average middle-class person. But I have to give him credit: he does get people thinking, even me. Even while I’m sitting there disagreeing with him and scrawling large rebuttals in the margins of his books, he’s got me thinking.

Scott

There’s an interesting aspect of a thing that we flew by very quickly, which is that you can’t borrow enough. One of the things that comes out in consumption smoothing is a thing called “liquidity constraints,” which is economic gobbledygook for saying that you can’t borrow enough money. But it has a wonderful side effect.

.jpg) Because you and I can’t borrow enough money when you’re younger, it makes the mathematics of leveling your consumption throughout your life essentially impossible. If you were to take an average person’s life-cycle profile, what you discover is that they can’t have a level standard throughout their lifetime. You’ll have an approximation, and so they’ll have one standard of living through their 20s, 30s, and early 40s, they’ll take a step up in their late 40s and into their 50s, and then there’s another big bump up later.

Because you and I can’t borrow enough money when you’re younger, it makes the mathematics of leveling your consumption throughout your life essentially impossible. If you were to take an average person’s life-cycle profile, what you discover is that they can’t have a level standard throughout their lifetime. You’ll have an approximation, and so they’ll have one standard of living through their 20s, 30s, and early 40s, they’ll take a step up in their late 40s and into their 50s, and then there’s another big bump up later.

The important thing here is that this is against our will!

We want to borrow more money. We have been fine and doing our mightiest to borrow as much money as possible, and very few people can achieve it, even with all these nitwit bankers wanting to lend you everything. So, we have this built-in safety lever in liquidity constraints. The only problem with it is that it is contingent on the policy risk that’s involved in Social Security benefits for the very young. Because if the promises aren’t fulfilled, then those numbers won’t materialize.

J.D.

This would be a good a time for you to explain what consumption smoothing is. This is actually a new concept to me; I’d never heard of it before.

I’ve been trying to balance lately, for myself, the notion that I’m that I’m done paying off my debt, and all of a sudden I have this positive cash flow, and I need to decide, what I’m going to do with that. How much of that can I use now, and how much of that do I need to save for the future?

Reading Spend ’til the End and learning about consumption smoothing really helped me realize I can use some of that money now. I don’t actually have to save it all for the future. And I have to figure out what the balance is.

Scott

And that’s the most difficult thing, because we’re always at war with ourselves. Part of us wants to, you know: “I want it all, I want it now.” The other part of us says retirement is more important. I find with reader letters that our population isn’t a smooth curve, isn’t a “mountain curve” of distribution. Instead, it’s bimodal.

You’ve got a group of people — admittedly small — who are over-saving and their standard of living should be higher. .jpg) And they’ll wind up either dying with a fortune or possibly becoming big spenders late in life or retiring early. They’ll have those options. Then there’s the larger group that feels entitled in some way and feels that they must have everything now, and so they’re always over-estimating, over-optimistic, about their future.

And they’ll wind up either dying with a fortune or possibly becoming big spenders late in life or retiring early. They’ll have those options. Then there’s the larger group that feels entitled in some way and feels that they must have everything now, and so they’re always over-estimating, over-optimistic, about their future.

Doctors are a great example of people who are over-optimistic about their future. It’s amazing. They treat human beings for major illnesses and many of them have yet to consider that at one point they will no longer be able to work. So they’re going along blithely spending all kinds of money without smoothing their consumption at all.

That goes back to the behavioral finance that you mentioned earlier. We’re just not geared to actually be able to to it very well, and worse, it’s not a simple problem, because there are a zillion different programs and things that affect our ability to smooth our consumption. Not to mention all kinds of unknowns, like the fact that your fifties is the most dangerous decade of your life, in finance.

There was one study done — I think it was the National Bureau of Economic Research that did it. They found an enormous amount of the distribution of wealth had to do with basically good fortune or bad fortune. And the most dangerous decade was the fifties because:

- That’s when people have the expensive divorces.

- That’s when jobs get tenuous for some.

- That’s when people become ill or are not capable of working as hard as they did when they were in their forties.

As I look around at people I’ve worked with over the last fifteen years, that’s exactly what’s happened. I knew some wonderful people who just got on the wrong side, whether they made a bad decision or if they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. But their career paths have been unfortunate.

And then there are other people of equal ability — and sometimes lesser ability — who have been startlingly more successful. A lot of it due to chance: marriage, your kids, things like that. It has nothing to do with return on investment, anything Ben Bernanke says, anything that anybody at Goldman Sachs says. It has everything to do with the human condition.

J.D.

Yeah. I think that a lot of times, when people make personal finance decisions, they don’t realize the human aspect of things. It’s going to play a large role, especially eventually.

I’m 39, so I don’t know all of those things that lie ahead of me when I’m between 50 and 60. For me, illness is something that I worry about; cancer runs in my family, and that could have a huge impact on what exactly I can do with my finances. If I end up going the way of all my male relatives, I dunno…

So, one last question. As you connect with your audience through your website and through speaking engagements and book signings and so on, what are the biggest concerns they seem to have? Are there certain concerns that come up over and over again? And what kind of advice do you have for them?

Scott

First, there hasn’t been an awful lot of response to the book to date, but the recurrent themes are still present just in the reader communication. The column is very widely distributed and it’s got a lot of regular readers. But some things come up again and again:

- People want to believe that buying lots of house is good for them.

- They want to believe that buying a second house is good for them.

- They want to believe that borrowing is good for them.

- They want to believe that they should take Social Security benefits as soon as possible because they’re sure they’re going to die early.

But they want to take that money and they don’t want to think about that decision as a financial decision. They get all tied up in the idea that they can take the money now. They don’t think about it actuarially. (That’s probably a good thing, because if we had 300 million actuaries in the country, it would be a really dull country.)

The reality is that the Social Security benefit delay is the best financial deal out there. Basically you give up a dollar of Social Security benefits and you have to spend a dollar fifty in investment money to get the same benefit as just delaying for a year. That’s a slam dunk.

That’s one of the other things in the book. You’re way ahead of the other people where you’re starting to think about all the alternatives. Most people don’t even stop to think about their spending agenda is way ahead of their income. So they’ve always got the next purchase planned, and they never get to what you might call the philosophical part, which is, “You know? Do I want to consume everything now or save some for later?

J.D.

Well, for me it’s actually been a struggle lately. I spent three years digging out of debt, and I was so focused on it, I had to curtail my spending. I didn’t curtail my luxury spending entirely (I don’t think that anyone could or should), but I focused on getting out of debt for so long there that once all of a sudden I had that free cash flow, it’s really been a challenge for me to say, “How much of this is going to go to savings and how much of it is going to go to improve my current lifestyle?”

That’s why reading Spend ’til the End came at just the right time. It seems to me the book is in many ways geared toward people in their fifties, but there’s still plenty to think about if you’re my age (39) or even younger. So the concept of consumption smoothing made me think, “Hey. It’s okay. I can spend a little bit of money on myself.”

Scott

We’re all just kind of muddling though and we use the best tools that are available at this particular moment, and we make the best decisions that we can, given the information that we have. Sometimes, that’s a disaster, but a lot of people out there are thinking that there is some cathedral of truth, where there is a final calculus.

We’re all just kind of muddling though and we use the best tools that are available at this particular moment, and we make the best decisions that we can, given the information that we have. Sometimes, that’s a disaster, but a lot of people out there are thinking that there is some cathedral of truth, where there is a final calculus.

I’ll get letters from people saying, “What exactly is couch potato investing?” And it’s like they got upset when I switched from the Vanguard 500 Index to the Vanguard Total Market Index. They think change invalidates. Change doesn’t invalidate — change just shows adaptation.

J.D.

Absolutely. I believe this, too. It seems especially in our political culture, we want absolutes. We want it to be this or that, we want things to be black or white. We’re very polarized.

But I think that there’s often — almost always — a continuum. There are stages in between. And so one of my mantras — it’s like the theme of my site — is “do what works for you”“.

For example, when you talk about paying down debt, the mathematical way to do it, of course, is to pay down the high interest rates first. But that never worked for me until I discovered Dave Ramsey, who says, “No, start with the small balances first.” And that really drives some people crazy because they think that doesn’t make sense mathematically.

Scott

It makes sense emotionally, because you get rid of all of it. You say, “I had eight debts, and now I’m down to three.” Eighty percent of the debt is still in the last three.

J.D.

Exactly. But on the other hand, it feels so much better. And you free up that cash flow, too. But for me I say, “Do what works for you.” Because there are multiple approaches.

What you’re trying to do is improve your financial situation, and there are multiple tools and multiple approaches to do it. Some will work for some people; for some people, paying off debt with the high interest rate first, it’ll work for them and that’s great. But if it doesn’t, don’t think that that’s the only way you have to do it.

I think the same goes for risk tolerance. There’s more than one way to invest, and your risk tolerance has to play a huge role in how you invest. There’s no one right way — you’ve got to take into account your risk tolerance.

Scott

Right. If you don’t take it into account, you’ll wind up abandoning the risk that provides the higher return at a very crucial time.

J.D.

To me, money reveals a lot about people: how they relate to money and how they interact with it. And how they change how they relate to it. My relationship with money now is completely different — it’s almost a polar opposite — from what it was five years ago. So, I think it’s encouraging to see that people can grow and learn and develop.

Scott

Yes. But just don’t assume that everybody can. Hope that you can help some.

J.D.

So far, I have been able to help some. I just hope I can help many more.

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)