Teaching kids about money: How to raise money-smart kids

A few years ago, I polled my Twitter followers to ask: “What did your parents teach you about money? Anything? Did it work?“

A lot of folks responded to say that their parents were poor examples:

- @MoneyMateKate wrote: My parents didn't teach me — I taught them! I was paying my own dental bills (no insurance) from age 12 onwards with babysitting dollars.

- @liberryteacher wrote: My parents never had any money, and life was hard. So they taught me by example that that was not a good way to live.

- @mike_strock wrote: My parents gave me money whenever I asked. Needless to say, that wasn't helpful later in life. I'm learning!

- @tcita wrote: My parents taught me absolutely nothing: no chores, allowance, budgeting, spending money, savings — nothing. Though I guess that taught me value of work.

But not all parents fail at training their children about money. Plenty of folks picked up good habits from the Bank of Mom and Dad. Here are some of my favorite anecdotes and tips:

- Pam from The Turtle Path (a running blog) told me: In junior high, my parents gave me $400 at the beginning of the year (instead of a weekly allowance). They told me I could do whatever I wanted with it, but they weren't giving me any more money the rest of the year, so don't ask.

- @Elle_CM wrote: My mom (and grandma) emphasized always saving a chunk of any income you receive. We used to make Saturday deposits at the bank.

- Via Facebook, Cynthia wrote: As kids, if we were at the store and saw something we wanted, my dad would say, “Did you bring your money?”

- @mattwakefield wrote: My dad taught me about the stock market by using a 1/100 scale model of the [stock] market. Got hooked early!

- @EverydayFinance wrote: My father insisted on no credit-card debt and said, “Everything in moderation.” It worked like a charm.

- @kingkool68 wrote: My parents printed family checks for my allowance. I could write checks to my parents in first grade! They also gave me monthly statements.

Teaching your children about money is one of the best things you can do to ensure their future success. Financially aware kids become financially aware adults.

How do you teach kids about money — especially if you haven't yet figured out money for yourself? This is a tough question for me to answer since I have zero experience raising children. That said, I've paid close attention to the experiences of my friends and family over the past twenty years. While I don't have any personal experience with this subject, I've observed what has and has not worked for others.

Teaching Kids About Money

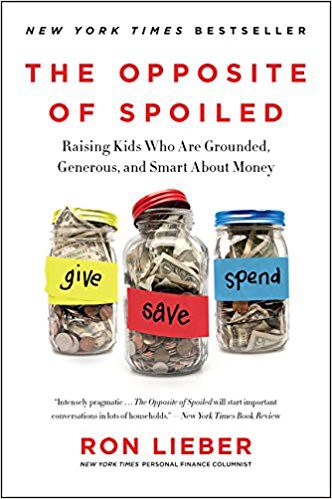

A few years ago, I chatted with New York Times columnist Ron Lieber about his book The Opposite of Spoiled, which is all about “raising kids who are grounded, generous, and smart about money”.

“How do children become spoiled?” I asked.

“They’re not born that way,” he said. “We do it to them. Nobody wants to raise a spoiled child, yet it happens all the time.”

“When we talk about spoiled children,” Lieber told me, “the opposite qualities are modesty, patience, thrift, generosity, perspective, perseverance, courage, grit, bravery, prudence, and so on.”

“The thing is,” he continued, “you can use money as a central tool to teach kids about every single one of these. Instead of shying away from the topic, what if we put money at the center of family conversations? What if we assumed not that money subverts values but contributes to them? Because it does. This is the path to financial literacy and financial education.”

From what I've seen, there are four steps parents can take to teach their kids smart financial habits:

- Set an example. Model the behavior you want your kids to learn: If you want them to save, save. If you don't want them to become compulsive shoppers, curb your own compulsive shopping.

- Be prepared. Have answers before you need them. Know how you're going to handle specific situations like allowances or begging for candy in the grocery store. (I know one couple who deflect begging by simply saying, “Sorry, that's not in the budget.” I love it!)

- Be consistent. Kids do best with clear, consistent expectations, so think carefully about your family's money rules before setting them. Don't be so rigid that there's no wiggle room but once you've set a policy, apply it consistently and fairly.

- Be honest. Share your success and failures. Tell your kids what you did right and what you wish you'd done differently. Explain your thought process each step of the way.

Most of all, make this learning process interactive. Involve your kids in frugal activities that teach them self-sufficiency, such as gardening, baking, home improvement, and so on. Teach them to comparison shop at by having them help at the grocery store. As they get older, make them financial apprentices: Show them how to pay bills, check a credit score, and buy a car. Teach them that managing a household is a team effort.

Providing Hands-On Experience with an Allowance

One of the best ways to teach kids about money is to give them hands-on experience with an allowance. When they have their own cash to manage, kids are better able to learn the value of saving and the difference between wants and needs.

There are two schools of thought about how allowances ought to be provided.

- The first says that the money should be tied to grades, chores, and behaviors. This gives kids an incentive to do the right thing. But critics argue that tying an allowance to these actions sends the wrong message. Kids should stive for good grades regardless of what (or whether) they're paid, say the critics, and doing chores is part of belonging to a family.

- The second camp says that you should give the allowance without expecting anything in return. Using this method, kids learn about money even if they don't make good good grades or do their chores. But some people believe this method leads to an “entitlement mentality” in which the kids expect something for nothing.

Most families are probably best off with some sort of hybrid approach: Provide a minimal base allowance that's paid no matter what, and then add incentive pay for certain chores and behaviors.

Tip: If you want to incentivize good grades without money, consider rewarding with something else your child values: a later curfew, a trip to a concert or pro sporting event, golf lessons, more time with friends. This should encourage the behavior you want without tying it to money.

Whichever method you choose, use the allowance as a chance to teach your children the value of money. Instead of letting them spend it on whatever they want, consider a system that divides the money for specific goals.

You might, for example, use three jars (or envelopes) labeled:

- Save (30%). This money is for long-term goals, such as buying a bike or a baseball mitt. Let the child decide on the goal — with your help.

- Share (10%). The money in this jar (or envelope) is for giving to somebody else. Your kid can decide where it goes — whether it's a charity or just somebody else in need (even a sibling!). The point is to share with others.

- Spend (60%). There are no restrictions on the money in this jar. Your child can spend it on comic books or bubble gum — whatever strikes her fancy.

A decade ago, my friend Lisa tried this system. She wrote an article here at GRS about how she had her kids divide their allowance into four jars: Spend, Save, “When I'm Old”, and Donate. (If you don't want to use jars or envelopes, you can now purchase money-savvy piggy banks with slots for Save, Spend, Donate, and Invest.)

Final Thoughts

Last month, my friend Doug from The Military Guide told me about how he raised his daughter to become a financially capable young woman.

“We got her involved from a young age,” Doug said. “My daughter got to see how my wife and I made financial decisions. But the best thing we did was to start her on an allowance. We gave her money and let her do what she wanted to do with it. She made some mistakes, sure, but we were there to help her. And I'm glad that she made those mistakes when she was thirteen years old instead of 23 or 33.”

I think Doug's approach was smart. So far, it seems to be paying off. Now that she's an adult, his daughter is making smart choices and is well on the path to future financial independence.

Many of us were raised with faulty and/or incomplete money blueprints. We entered adulthood not knowing how to handle money responsibly. I believe one your most important jobs as a parent is to give your children accurate, reliable money blueprints that will help them establish a solid financial foundation — then construct a life where they don't have to worry about money.

Ultimately, the most important thing is to get your children thinking about and interacting with money from an early age. It's better for them to make money mistakes at thirteen years old than at thirty!

Become A Money Boss And Join 15,000 Others

Subscribe to the GRS Insider (FREE) and we’ll give you a copy of the Money Boss Manifesto (also FREE)